It was intended as an ‘alternative daily cover’ for the sanitary landfill of Carrascal town in Surigao del Sur, but a local environment officer points out there is no study that it is suitable for such use. Rep. Prospero Pichay says it is not fertilizer but waste, and wants South Korea to take it all back.

By Carmela Fonbuena/Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism

AT A GLANCE:

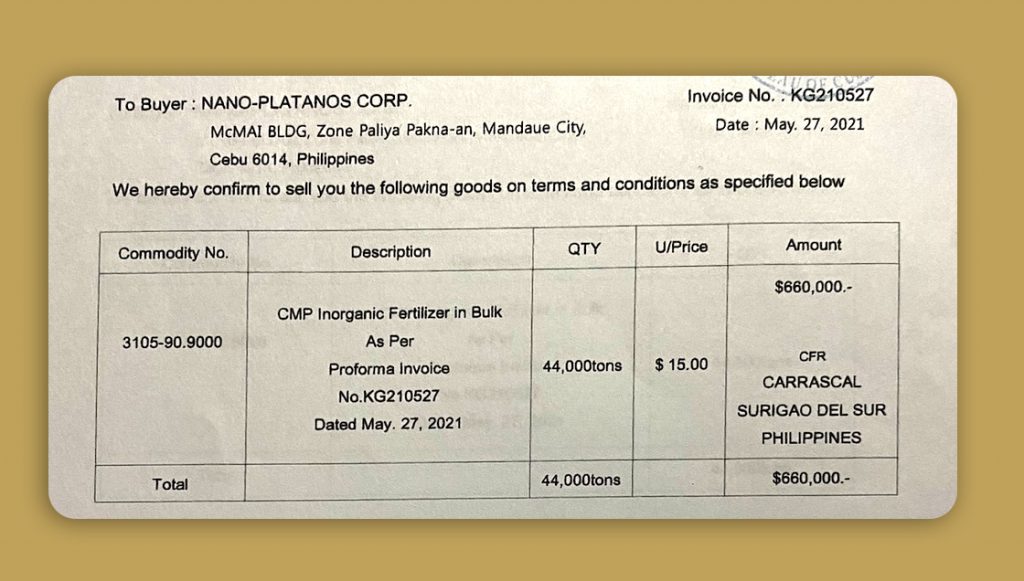

- A huge volume of “CMP inorganic fertilizer” from South Korea was shipped to a landfill in Carrascal town in Surigao del Sur in June 2021.

- Cebu-based consignee Nano-Platanos Corp. bought the fertilizer for $660,000 or about P33 million, then donated it to the municipality of Carrascal.

- Carrascal wants to use it as an ‘alternative daily cover’ for its sanitary landfill, but a local environment officer says there is no study that it is suitable for such use.

- The chief of the Carrascal Municipal Environment and Natural Resources claims the fertilizer is also intended for the rehabilitation of mining areas.

- Rep. Prospero Pichay says it is not fertilizer but waste, and wants South Korea to take it all back.

Forty-four million kilos of “fertilizer” from South Korea were shipped to a sanitary landfill being built in Barangay Bon-ot of mining town Carrascal in Surigao del Sur, prompting a new foreign waste dumping investigation in the Philippines and calls to return it to South Korea.

Documents obtained by the Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism (PCIJ) showed that Cebu-based Nano-Platanos Corp. bought a huge volume of “calcium magnesium phosphate (CMP) inorganic fertilizer” from South Korean company Korean Gypsum Inc. for $660,000 or about P33 million. The company then donated the entire volume to the Carrascal local government unit (LGU), which intended to use it as an “alternative daily cover” for its sanitary landfill.

It is not proven to be suitable for such a purpose, however.

“There was no existing study on the CMP as an alternative cover of residual waste,” read a June 22 report prepared by Kenneth Salvani of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) field office in nearby Cantilan town.

The report recommended further study on its use on landfills.

The Environment and Management Bureau (EMB) Central Office of the DENR has begun an investigation into the shipment.

CMP inorganic fertilizer is a type of soil conditioner used to correct the acidity of soil. The shipment from South Korea received certification from the Fertilizer and Pesticides Authority (FPA) of the Department of Agriculture (DA), but the local field office of the DENR and Surigao del Sur Rep. Prospero Pichay Jr. raised concerns about foreign waste dumping.

The DENR in Cantilan town cited the extraordinary volume of the shipment that was shipped to the landfill. Pichay was also suspicious of the “small company” from Cebu that donated the fertilizer.

“I cannot allow the Province of Surigao del Sur to be used as a dumping ground of the waste materials of Korea,” said Pichay. He said South Korea should take back the shipments.

The chief of Carrascal’s Municipal Environment and Natural Resources Office (Menro), Lawrence Brion Cortes, said they accepted the donation thinking they could use it as soil cover. He told the PCIJ they would wait for the studies to be completed before using it in the landfill.

‘Low to moderate toxicity’

Mountains of the greyish powdered solid now sit on the grounds of the “Eco-park” inside the area of the sanitary landfill, drawing concerns that runoff from the huge volume of fertilizer during the rainy season will pollute nearby waterways.

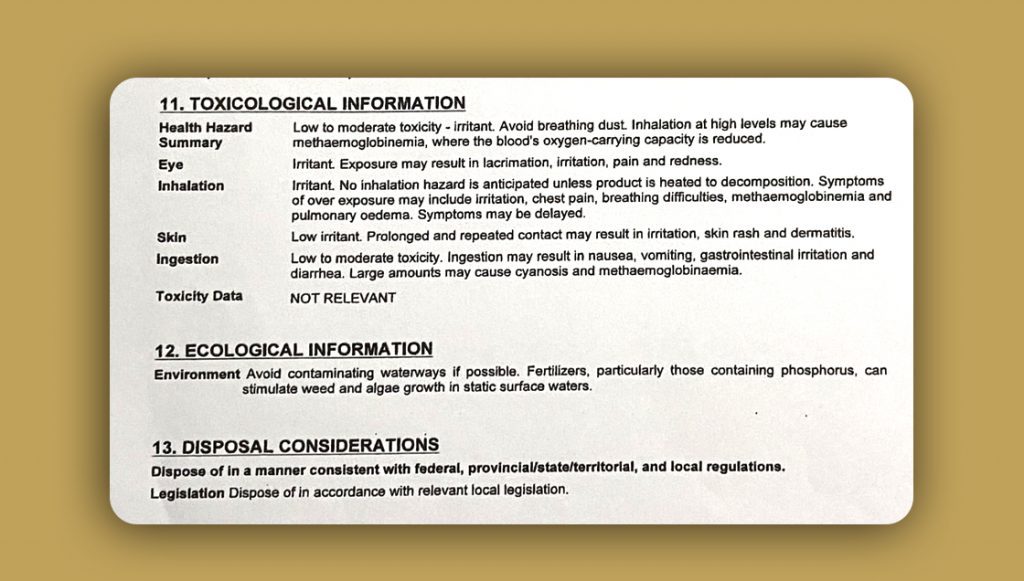

The DENR tested samples from the shipment and found that the fertilizer was neither hazardous nor dangerous. However, a material safety data sheet issued by Farm Hannong in South Korea, the manufacturer of the fertilizer, gave instructions to “avoid contaminating waterways if possible.”

“Fertilizers, particularly those containing phosphorus, can stimulate weed and algae growth in static surface waters,” it said.

Cortes said they would cover the fertilizer to prevent leaching.

The toxicity of the fertilizer is “low to moderate,” based on the safety data sheet. In an extreme scenario where it is inhaled at high levels, it “may cause methaemoglobinemia, where the blood’s oxygen-carrying capacity is reduced.”

If stored in the open, a tarpaulin cover was recommended to reduce dust, although the landfill is far away from residential areas.

The fertilizer will sit on the grounds of the landfill unless actions are taken to remove it or the municipality finds use for it.

Cortes told PCIJ they could also use the material to rehabilitate mining areas in the town, citing a similar shipment that arrived in October 2019.

“Hindi naman po soil cover lang ang purpose nito. Bale tinanggap po ito ng LGU kasi if ever na hindi ito suitable for soil cover e pwede naming ibigay sa mining company para magamit nila sa kanilang mining rehabilitation (Its use is not limited to being soil cover. The LGU accepted it because it can also be used to rehabilitate the mining companies if it is not suitable soil cover),” said Cortes.

“Either way naman po talagang magagamit. Hindi naman po talagang masasayang (Either way, we will use it. It will not be wasted),” he said.

The 2019 shipment, which was also donated by Nano Platanos Corp., was received by Marcventures Mining and Development Corp. It was one of the mining companies that the late Environment Secretary Regina “Gina” Lopez sought to close down.

The fertilizer received by Marcventures is unutilized or underutilized.

“It is worthy to note that the first batch of the donated CMP given to the [Marcventures] last 2019 was allegedly unutilized until to date due to the Covid-19 pandemic based on the report of the [Marcventures] dated January 15, 2021. As of to date, there are still no updates relative to the utilization of the CMP,” based on a July 5 DENR report. The report also recommended returning the fertilizer to South Korea.

Pichay, who himself used to be president of nickel mining company Claver Mineral Development Corp., said there was no mining area that needed rehabilitation in the province “because most of the area is not yet mined out.”

Foreign waste dumping

The investigation underscores the challenges of policing international trade of waste between countries.

Some cases of foreign waste dumping are more obvious, such as the notorious “Canada waste” in 2015. The shipments of household wastes that arrived in the Philippines were declared as plastic recyclables. South Korea also figured in a waste controversy in 2018, when assorted wastes were declared as synthetic plastic flakes. Both countries eventually took back the waste shipments.

Less obvious is the technical smuggling of agricultural wastes, said Bureau of Customs spokesperson Vicente Maronilla.

“People have this impression that if it is organic or chemical based, if it relates to use in agriculture, then it is okay. It is less toxic. Apparently, hindi ganoon (it is not the case),” Maronilla told the PCIJ.

“Even the ones they claim are organic fertilizer, we’re now discovering through DENR that it also ruins certain balances [of the soil] if you don’t use it correctly,” he said.

These kinds of agricultural imports also fall under waste trade, Maronilla said. “It is technical smuggling. Because of multi-use products, nagiging technical na rin ang smuggling e (technical smuggling can happen)…. Sometimes it’s waste. Dina-dump na lang sa atin (They dump it in the country),” he said.

Customs is also investigating the shipment in Carrascal, although Maronilla said the DENR was leading the probe.

A July 5 report of the DENR field office in Cantilan took issue with the fertilizer going to a landfill.

“The volume of the questioned ‘fertilizer’ does not justify their excuse that it will be used as ‘fertilizer.’ In fact, the alleged ‘fertilizer’ was only dumped in a landfill in Carrascal. Clearly, their intention is to make Carrascal, Surigao del Sur a dumping ground,” according to the report signed by environment officer Marslou Bonita.

The report cited communications between the DENR office and the South Korean supplier. “In fact, the Korean principal when asked if the said ‘fertilizer’ can be distributed to farmers, he alleged that it can only be used to cover landfills. Thus, the following circumstances strengthen the undersigned’s belief that they are only making Surigao del Sur a dumping ground,” the report added.

Roldan said fertilizer is a general term that does not necessarily involve farm use. CMP inorganic fertilizer is material intended to be a soil conditioner. “These are soil elements that can be used to amend the soil – if the soil is lacking in some texture,” he said.

Asked about issues raised against the volume of the fertilizer and the purpose for importing it, Roldan said those were no longer FPA’s concerns.

“Number one, it (Nano-Platanos Corp.) is duly registered. Number two, the analysis is the same as what they have submitted to the FPA. Number three, there are no heavy metals in a level that is deleterious to environmental hazard,” Roldan said.

This attitude is problematic, however, and has made monitoring foreign waste shipments difficult, according to government officials privy to the investigation but were not authorized to speak publicly on the investigation.

Agencies in government cannot work in silos, they said. They said the DA should have alerted the EMB given the huge volume of the fertilizer, scrutinized how it was intended to be used, and anticipated possible problems.

The moment an agricultural product is certified by the DA, there’s little that can be done to stop the Bureau of Customs from releasing the shipments.

“Wala rin kami magawa kapag ganiyan kasi may permit e. (We can’t do anything in that case because it has a permit.) It was given the go signal,” Maronilla said.

Pichay’s complaint

On the ground, the investigation has become political because of Pichay’s involvement as complainant. The mayor of Carrascal, Vicentel Pimentel III, is the nephew of Surigao del Sur Gov. Alexander Pimentel.

Pichay filed a complaint with Environment Secretary Roy Cimatu and Customs chief Leonardo Guerrero in a letter dated July 13.

He demanded immediate investigation. “[C]onsidering the volume of said fertilizers, it is obvious that these are wastes being dumped in our country,” he said.

Pichay said the Cebu company, Nano-Platanos Corp., was suspicious. “Ikaw Filipino businessman, mag-import from Korea ng fertilizer. Tapos ido-donate niya? Ang liit-liit na kumpanya (You’re a Filipino business. You import fertilizer from Korea. You’ll donate it? It’s a very small company),” he said.

PCIJ tried to reach the company through its office in Cebu twice, but was unable to reach its representatives. The author left her mobile number with two personnel from another company, which apparently shared the telephone number indicated in the customs papers.

PCIJ also reached out to the South Korean embassy in Manila, but did not receive a response as of posting. Any comment from the embassy will be added to this report.

Pichay said he was familiar with the fertilizer. He earlier helped the same Cebu company in persuading Marcventures to receive the first shipment in 2019, which he said was a mistake.

The first shipment was reportedly about 20,000 tons or 20 million kilos, based on a 2019 DENR report, although PCIJ did not obtain documents on the shipment.

Pichay said he was surprised that another shipment arrived in June when Marcventures had yet to utilize the first shipment.

While DENR laboratory tests showed that the samples were not hazardous or dangerous, Pichay echoed concerns about the volume of the shipment.

“Kapag uulan… sa dami ng volume, madami din ang toxic… (When it rains… given the huge volume, a significant amount of toxic [materials will be released]),” Pichay said.

20 million kilos in 2019

Cortes said the LGU was surprised by the complaints. “Hindi po namin naiintindihan bakit maraming complaints e noong sa Marcventures na unang shipment e na-prove naman na hindi po ito toxic (We don’t understand why there are many complaints when it was proven from the first shipment with Marcventures that the material is not toxic),” he said.

“Kaya po tinanggap namin ito kasi ‘yung 2019 na fertilizer is na-prove naman na okay siya. Same source kaya po tinanggap namin (The reason we accepted it was because the fertilizer back in 2019 was proven to be okay. It came from the same source so we received it),” said Cortes.

The first shipment arrived in October 2019. It was the subject of a Facebook post that raised concerns against toxic wastes, prompting protests in the province and a succeeding DENR investigation.

The material was found to be non-hazardous, but the circumstances surrounding the donation raised questions even then.

A 2019 DENR report showed that the fertilizer was originally supposed to be delivered to Libjo Mining Corp., operating in the province of Dinagat Islands, for the purpose of rehabilitating its mining areas. Nano-Platanos was unable to provide a document to prove that the mining company, which was also in Lopez’s list of companies to be shut down, agreed to receive it.

Pichay said several mining companies, including one operated by the incumbent mayor of Carrascal, were offered to receive the donation but they supposedly refused because they feared that their mining permits would be compromised if the shipment turned out to be problematic. (PCIJ sought the mayor to comment on the probe, but his staff referred us to the MENRO chief.)

Pichay said the shipment was eventually unloaded on a lot owned by his brother in Cantilan town. It prompted complaints from the neighborhood because of the dust, which caused itchiness, he said.

He then persuaded Marcventures to take the fertilizer, which was moved to its mining grounds in Brgy. Pili and Brgy. Sipangpang in Carrascal, where its reforestation activity and nursery are located.

Pichay said the shipment must be returned to South Korea or more shipments of the fertilizer – he claimed seven more shipments were due to arrive – would be dumped in the province.

Following the complaints, Cortes said he would not recommend receiving more donations of the fertilizer. “Kung sa akin lang siguro, huwag na (If it were up to me, we shouldn’t receive more shipments).” END

This report was produced with the support of Greenpeace Southeast Asia-Philippines. The Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism had full editorial independence. Greenpeace Southeast Asia-Philippines, their officers, and employees accept no liability for any loss, damage, or expense arising out of, or in connection with, any reliance on any omissions or inaccuracies in the material contained in the report.

0 Comments