Second of Two Parts

APARRI, CAGAYAN — “Ipalubos yo kadi nga dadaelin da ti panagbiag mi (Will you allow them to ruin our lives and livelihood)?” a protester on loudspeaker in a mini truck roared to a crowd of protesters during a rally dubbed “Alay Lakad para sa Kabuhayan, Kalikasan, at Kinabukasan” during the celebration of Earth Day on April 22.

The crowd of nearly 2,000 residents, church people, and representatives of environmental groups roared back. “No! Oppose black sand mining!”

The crowd gathered at the ungodly hour of 4 a.m. to walk 13 kilometers with their placards and posters to oppose a dredging project of the provincial government, which fisherfolk and environmental groups suspect was a cover for black sand mining despite denials from regional and provincial officials.

The early call time was an attempt to avoid the punishing summer heat. Father Manuel Catral of the San Pedro Telmo Parish worried that people might not finish the activity, but the crowd proved to be determined to make their voices heard.

Police vehicles cruised back and forth to different villages to fetch and drop people off at the town’s welcome arc where a first-aid station was installed.

Contractors bear full cost of project

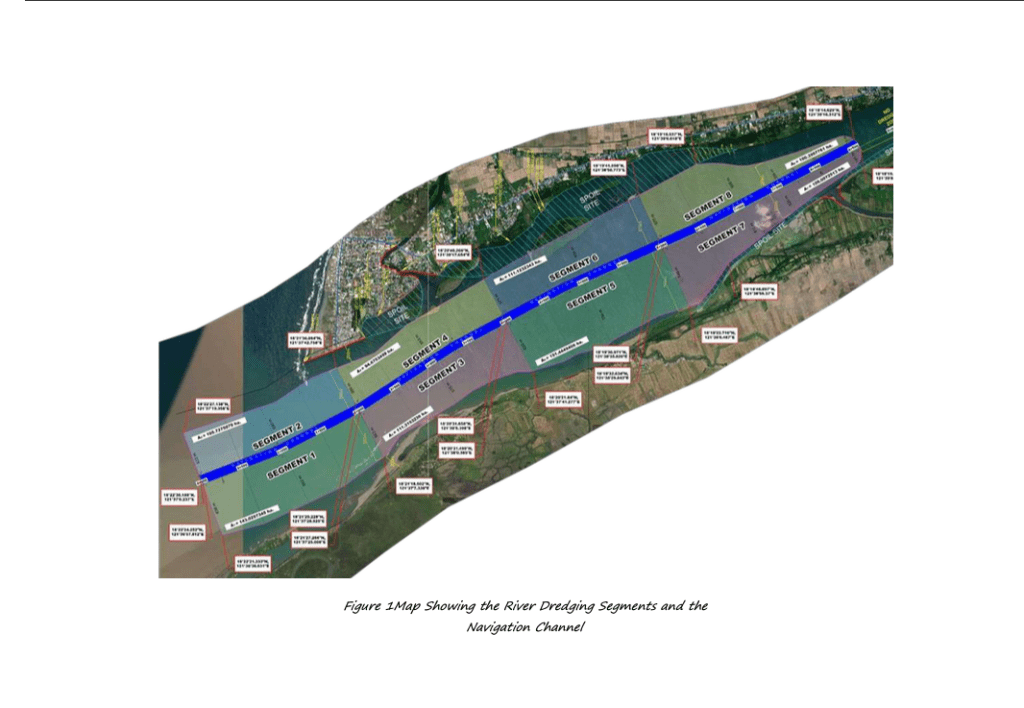

The provincial government’s dredging project covers some 31.87 kilometers of the Cagayan River in the towns of Aparri, Camalaniugan, and Lal-lo. It will remove sandbars that obstruct the flow of floodwater to the Aparri Delta and the Babuyan Channel.

DENR Region II Director Gwendolyn Bambalan said the dredging activity is part of the province’s flood mitigation project “to prevent such flooding like what happened after Ulysses.”

In November 2020, Cagayan province experienced its worst flooding in four decades during the onslaught of typhoon Ulysses, which affected at least 580,000 people and killed 24 individuals in the region.

Authorities identified at least 19 sandbars along Cagayan River covering some 275 hectares and an estimated seven million cubic meters of sand materials to be dredged.

The Inter-Agency Committee on the Restoration of the Cagayan River, chaired by Cagayan Governor Manuel Mamba St. and vice-chaired by the DENR Region II Director, oversees the project.

On June 8, 2020, Gov. Mamba wrote to former Environment Secretary Roy Cimatu, saying that the provincial government considers “a possible venture with the private sector” to undertake “desilting and dredging” of the heavily silted Cagayan River “without cost from the local government.”

Mamba said the involvement of the private sector is due to the provincial government’s “lack of necessary funds” to address the problem that “poses great peril to communities around the rivers due to flooding and soil erosion.”

Based on the Memorandum of Agreement (MOA) signed between the government and the dredging companies, the contractors will “undertake the project without any funding from the government and bear the full cost of the project including the disposal of the dredged materials.”

What do the contractors get in return? Bambalan said “it is up to the dredging companies how they will use the dredged materials – whether sell them or bring and use them somewhere else.”

“In fact, nagrereklamo ang mga dredgers kasi puro burak (the dredgers complained because it was swampy). But they have to recoup the investment,” said Bambalan.

Mamba stressed that the dredging activity “is not only meant to be a river restoration and flood control project” but it is also “envisioned to be the enabling activity to ensure the re-opening of the Aparri port and establishment of a functioning international seaport.”

Dredger vessels at sea

Some fisherfolk believe that the large-scale dredging operation is not just a river rehabilitation project but “a cover for a black sand mining operation.”

Black sand or magnetite sand is used as an additive for steel and concrete products. It is also widely used in processing paints, ink, magnets, paper, jewelry, and cosmetics. The Philippines is one of the few countries in the world – including Indonesia, Japan, and New Zealand – with huge magnetite sand deposits.

As of June 2022, there are 12 approved Mineral Production Sharing Agreement (MPSA) for offshore magnetite mining, eight of which are in Cagayan province while four are in Leyte. The approved MPSAs for magnetite mining in Cagayan cover some 50,502 hectares in seven towns, including Aparri, according to data from the Mines and Geosciences Bureau (MGB).

Geric Umoso, a 24-year-old fisherman, said he and his fellow fishers saw a dredger ship exit the river and suck sand at sea one night in July 2021 at around 10 p.m.

“The ship’s lights were all on. We could hear and feel the vibration in the water as the vessel collected sand,” said Umoso. “If the purpose is really to rehabilitate the river and address the flooding problem, why are they collecting sand from the deep sea?”

DENR’s Bambalan said it was a misunderstanding. The area Umoso described is supposedly the navigational channel that project contractors must dredge to deepen the passage for huge vessels.

“As of now, ang dini-dredge pa lang ay ang navigational channel. Hindi pa nga nakakasimula sa segments (They’re only dredging the navigational channel now. They haven’t even begun with the segments). It is the navigational channel but it is within the river. Wala silang (They have no) dredging outside of the river,” said Bambalan.

Bambalan also said the vessel the fisherfolk saw anchored at sea was the mothership that hauls the dredged sand materials from the river to other countries.

“The mother vessel is too big na hindi siya pwedeng pumasok sa loob (it cannot enter the river). But that [vessel] is not dredging. Ang nag-de-dredge ay yung dalawang maliit (Two other smaller vessels are doing the dredging),” she said.

Hongchang, the mothership, is a 25-year-old bulk carrier currently sailing under the flag of Panama. It can haul up to 64,000 metric tons of sand materials.

Bambalan said the mouth of the river is only four meters deep because of increased sedimentation due to soil erosion. The advisable depth is 12 meters.

In response to PCIJ’s queries, Riverfront Construction Incorporated (RCI) said one of the provisions in its MOA is: “the disposal of the dredged materials shall be outside Cagayan.”

To do this would require a mother vessel, which is larger and not capable of navigating into shallow rivers, to collect and transport dredged materials to its designated disposal site, RCI said in a written reply.

“In summary, other than the transfer of the dredged materials from the dredger to the mother vessel on standby in the sea, no dredging activity is being undertaken elsewhere than in the Cagayan River,” the company said.

RCI further said the disposal of the dredged materials is properly coordinated and monitored by the Inter-Agency Committee (IAC), and that a ship inspection was conducted in April 2021 before the project began.

As part of the IAC’s protocol, RCI said the MGB periodically inspects the vessel prior to shipping out of dredged materials. This is “to ensure our compliance with all the permits and regulations and to make certain that no black sand mining is being undertaken.”

PCIJ also tried to reach Great River North Consortium (GRNC) for comment, but we could not get its exact contact details. DENR’s MGB provided PCIJ a copy of its certificate of accreditation, containing only a general address with no street number. MGB also does not have the company’s contact number or email address.

Not convinced

Father Catral, who heads the Cagayan Advocates for the Integrity of Creation, admits that the Cagayan River mouth, an estuary where the freshwater meets the ocean, “is very shallow and has to be dredged” so that boats can pass without difficulty.

But he was not convinced of the explanations provided by the DENR and RCI. “The problem is that the dredging operation, which is already in its first year, is not at the river mouth,” Catral said.

According to the EIS prepared by RCI, one of the contractors, the site of its dredging operation should be upstream and “approximately 6.0 kilometers from the river mouth.”

Umoso claimed the vessel they saw in July 2021 was clearly operating in the Babuyan Channel, outside its supposed area of operations.

On May 2, 2022, Father Catral also sailed with some fisherfolk to check the location where the dredger vessels allegedly conduct siphoning at sea during nighttime.

“The location where the fishermen saw the vessels collecting sand materials was several hundred meters away from the estuary. And it is already part of the Babuyan Channel,” Father Catral claimed.

In an April 2022 statement, the fisherfolk said: “Sumisipsip ang mga barko sa mismong pinagkukunan namin ng isda. Sa lugar na tirahan ng mga sapsap, riting, at mollo, lampas sa kung saan nagsasalubong ang tubig ilog at dagat (The vessels siphon in the very spot where we fish. In the habitat of the sapsap, riting, and mollo fish, beyond the spot where the river and the sea meet).”

‘I will resign if they can prove it’

The provincial governor, Manuel Mamba Sr., had repeatedly denied that the dredging project was a cover for black sand mining.

“Tell them this! I will resign as governor if they can prove it. Or if you want, I will kill myself,” Mamba told PCIJ in an interview in November 2021.

Mamba also challenged critics, including the Catholic priests in Cagayan province, to join the authorities during the inspections of the vessels.

“They should go on board the vessels and audit if there is really a separator that is capable of collecting black sand,” Mamba said in Filipino.

The governor was referring to the magnetic separator, a piece of equipment that can collect black sand from the sediments. It can be installed on any dredger vessel.

“There might be black sand in what the companies collect from the river but they are not processing the sand material in Aparri because the project is about restoring the river and mitigating the flood,” he stressed.

DENR’s Bambalan also denied the mining allegation. She told PCIJ that the MOA with the dredger companies “bans the processing of dredged materials.”

“We can guarantee that there is no black sand mining because there is no material processing at the mouth of the river. The dredger vessels collect the sediment and transfer it to the mothership,” she said.

The disposal of the dredged sand material “is the prerogative of the dredging companies,” according to Bambalan.

“As to where the contractors bring the dredged material, we do not discuss that in our meetings because it’s their call. We are here to ensure that they are compliant with the regulations,” she said.

A little sacrifice?

The fisherfolk community has demanded an immediate halt of the river restoration project. Photograph by Mark Z. Saludes/PCIJ

Mamba said his office is already addressing the problems of the affected fisherfolk in Aparri, while Bambalan reassured the affected communities that the “minimal disturbance” due to the dredging activity is only “temporary.”

“Pero eventually, magse-settle din naman yan. Kung ikukumpara mo siya with all these infrastructure sa Metro Manila, lahat tayo nabulabog (But it will eventually settle. If you compare it with all these infrastructure [projects] in Metro Manila, all of us are disturbed). We have to sacrifice a little,” she said.

On Feb. 7, 2022, Umoso wrote a letter to concerned agencies decrying the economic impact of the dredging activity to the fisherfolk. His group also requested the suspension of the river restoration project. “We demand an immediate halt of the project because it gravely affects the environment and our livelihood,” he told PCIJ.

For its part, RCI said it has taken a number of initiatives to support the local government units and the people. The company said it has provided rice and other food items to LGUs and NGOs, jobs for locals, sewing machines, feeding programs, and noche buena packs, among others.

As required, RCI also posted a P20 million cash bond for the issuance of a Notice to Proceed to commence dredging activity “to make sure we observe our obligations and do not disregard rules.”

The concerns of the fisherfolk and environmental groups have already reached the DENR and other concerned government agencies, Bambalan said, noting that the DENR has plans to address the issue with the Department of Trade and Industry (DTI).

In two separate letters addressed to Umoso and Aparri Mayor Bryan Dale Chan, the regional director of DTI said a sub-committee under the Build Back Better Task Force in the region had convened “to craft a Social Development Plan that will secure immediate response and alternative livelihood” for those affected by the river restoration project.

In the meantime, the way of life of Aparri fisherfolk is on pause. – with additional research by Elyssa Lopez

This article is published with support from the Philippine Center of Investigative Journalism

0 Comments