“We need heroes.” I kept telling myself after reading a UN Climate panel report that concluded that the Earth is definitely going to reach 1.5 degrees Celsius by 2040.

If the human family is really serious about saving the planet from an anthropogenic catastrophe that is certain to happen, we need warriors and heroes with superhuman powers, or perhaps, a miracle.

Then names and faces came out flashing in my memory. Names and faces of activists and environmental defenders who have been vilified, attacked, killed, or worse, disappeared.

They do not have superhuman abilities that can reverse the current state of planetary health or undo the destruction human beings have done to the environment.

They do not have the powers of Poison Ivy, a cartoon character who has the ability to control and mutate all forms of plant life on a molecular level and punish people with her ability to transfer poison through touch.

Wait… yes, I know. Poison Ivy is not a superhero. She is a supervillain in all movies and TV series. But is growing huge plants from small seeds in a matter of seconds an evil act?

We vilified Poison Ivy like how governments and capitalists defame environmental defenders and land rights activists as communists, terrorists, or anti-development conspirators.

From 2016 to 2020, at least 186 environmental defenders have been killed and thousands of human rights violations related to the defense of the environment and human rights have been documented.

Many of those killed activists were tagged as communists, terrorists, or supervillains who were threats to national security and enemy of development.

One of those faces that my memory made me remember was Datu Victor Danyan, a slain T’boli Manobo leader for asserting the rights of his indigenous village in Mindanao.

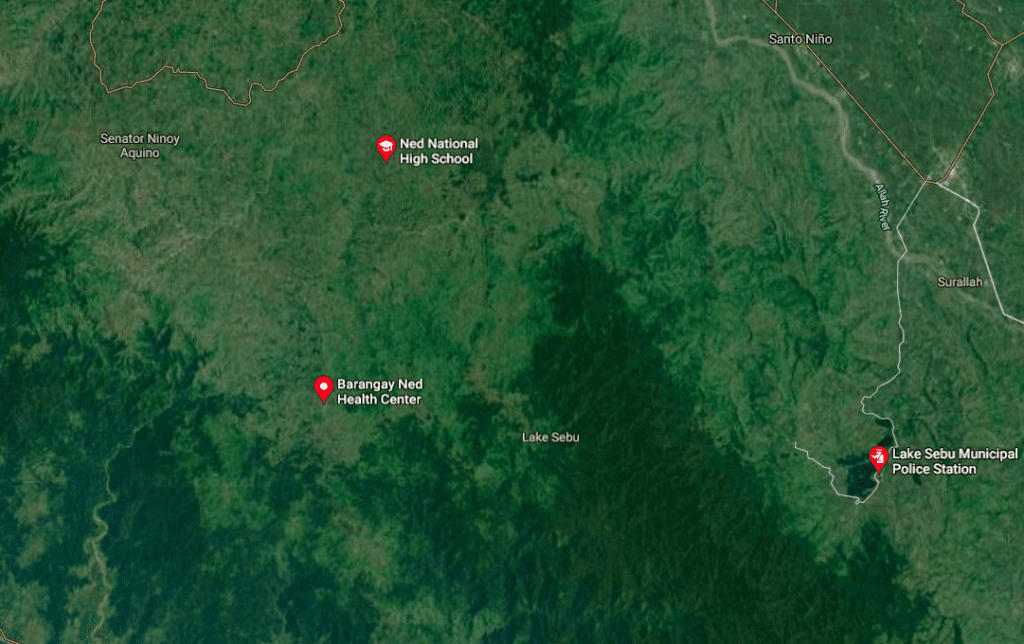

On December 3, 2017, a composite team of the Philippine Army and Marines conducted a military operation in Sitio Datal Bonglangon, Ned village in Lake Sebu.

The Philippine Army claimed its troops responded to a report that there were sightings of armed men in the area.

It said at least 30 communist rebels hiding in bunkers fired at government troopers during a maneuver to support another army unit.

The firefight lasted an hour and left 10 dead bodies – eight were alleged members of the New Peoples’ Army and two soldiers.

Contrary to the military report that it was an encounter with the rebels, witnesses stressed it was “an attack to silence” the indigenous community.

In my interview with Alicia Danyan in January 2018, she said her father and other villagers went to the farm to harvest crops.

Alicia is the 16-year old daughter of Rudy Danyan, who was among those who have been killed.

“At around 11 o’clock in the morning, we heard gunshots. It was coming from the direction of the farm where my father was working,” said Alicia.

Minutes later, soldiers started shooting at the people in the village. Alicia’s 11-year old brother was shot in the leg.

“We heard someone shout that Datu Victor was shot. Then there was chaos. I heard people crying for help,” said Alicia.

Others who were killed were Victor Danyan Jr., Artemio Danyan, Pato Celardo, Samuel Angkoy, Toh Diamante, and Mateng Bantal.

In the narrative of the military and the government, those who have been killed were villains – communist rebels who were terrorizing their own village.

But for the members of the T’boli Manobo indigenous community in Ned village, they were heroes who died defending their ancestral lands.

Hours before the bloodshed, Ned village captain Bebot Lobreta met with tribal leader Datu Victor Danyan.

Adina Ambag, head of the T’boli-Manuvu Sdaf Claimants Organization (TAMASCO) and sister of Datu Victor, said villagers were also present at the meeting.

Lobreta was there to convince Datu Victor to renew their contract, which had already expired years ago, with a coffee plantation owned by David M. Consunji Inc. (DMCI).

About 1,600 hectares of ancestral land of the T’boli tribe is being used by DMCI to plant coffee trees for Nestle Corporation.

In July 2017, the indigenous people of Sitio Datal Bonglangon reclaimed some 300 hectares of the land. They cut the coffee trees and replaced them with corn.

Datu Victor and the T’boli Manobo community led a province-wide campaign opposing DMCI’s coal mining concession in Ned village.

Ambag in 2018 told me that DMCI has attempted to take the land but resistance from the indigenous community was strong.

“We are taking what is rightfully ours. We still have 1,300 hectares to reclaim,” said Ambag.

KALUMARAN, a Mindanao-wide alliance of tribal groups, said the agreement was for DMCI to pay the tribal community some US$270 per hectare each year for using the land.

However, the corporation stopped paying the indigenous community after it managed to acquire a huge portion of the ancestral domain.

Contracts were not renewed because DMCI claimed full ownership of the land, according to the group.

DMCI started its operation in the mid-1970s after the late dictator President Ferdinand Marcos awarded the Timber License Agreement that gave the corporation authority to log 150,000 hectares in Daguma Mountain Ranges.

In the 1990s, the corporation started to run commercial agriculture covering a total area of 10,990 hectares in the provinces of Sultan Kudarat, South Cotabato, and Maguindanao.

The T’boli Manobo people became slaves in their own ancestral land. Most of the families in their village became workers in the coffee plantation.

“The corporation does not pay us for the lease of the land. Instead, they took us as coffee bean pickers and paid us with some kilos of rice every day,” said Ambag.

Ambag claimed DMCI prohibited planting crops, vegetables, corn, and other food plants. “That’s why we decided to fight for our rights and food security.”

The United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization reported in 2016 State of the World Forest that there was a net forest loss of 7 million hectares per year in tropical countries.

The report indicated that the greatest net loss of forests was in the low-income group of countries. “Large-scale commercial agriculture accounts for about 40 percent of deforestation,” the report said.

In the southern Philippines, about 500,000 hectares of land in the five regions of Mindanao are covered with agricultural plantation crops for the export market.

Faith-based REAP Mindanao Network said that it is equivalent to 12 percent of Mindanao’s total agricultural land.

Major commercial plantation crops that can be found are rubber, coffee, cacao, pineapple, sugarcane, and Cavendish banana.

More than half of these commercial agriculture plantations can be found in Northern Mindanao and the SOCSKSARGEN regions where Lake Sebu is situated.

Based on a report released by REAP Mindanao Network in 2016, land areas covered by commercial plantations have increased by 79 percent in just 10 years.

Almost half of the area used for commercial agriculture or 214, 315.6 hectares are covered with rubber plantations in 2016 from 81, 667 hectares in 2006.

There was an estimated 85 to 90 percent of the total land area used for commercial agriculture plantations across the country is within the ancestral land domain.

In 2014, Kalipunan ng mga Katutubong Mamamayan ng Pilipinas (KAMP) reported that 39 out of 63 priority mining operations in 2010 are within indigenous peoples’ domain.

I don’t think Datu Victor Danyan and the seven other members of the T’boli Manobo community in Ned village who were killed in December 2017 were villains.

From where I am standing, they are the real-life superheroes that this planet needs in order for our generation and the next younger generations to survive.

We need more warriors, like the eight martyrs of the T’boli Manobo indigenous community in Ned village, who are willing to fight and die for their ancestral lands.

We need more environmental defenders across the globe that despite vilification and harassment from the governments and capitalists, remain steadfast in their commitment to the protection of the environment.

We need to be like Poison Ivy.

Mark Saludes is a writer and visual journalist whose works focus on the environment, Indigenous Peoples, social justice, faith and religiosity, and the climate crisis. He is the chief of staff of the Laudato Si Information and Media Resource Center that runs oeconomedia.org.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official editorial position of OeconoMedia.org

0 Comments