She pulled out the drapes to cover the window but she couldn’t stand the noise of the smashing and plunking sound of rainwater.

Marinel Ubaldo got distracted by the heavy downpour while writing a speech she was about to deliver before the U.S. Senate subcommittee hearing.

Heavy rains bring back the fears and anxieties she felt eight years ago during the onslaught of one of the strongest and deadliest typhoons ever recorded in history.

She was a graduating high school student when Super Typhoon Haiyan hit the Philippines in November 2013 that killed more than 6,000 people and displaced thousands of families.

The 24-year-old environmental activist remembered “the calm the night before the typhoon” struck her village in Salcedo town, Eastern Samar province.

“My whole family was already in the evacuation center, which was just 10 meters away from our house, hours before the storm landed,” she said.

Marinel brought a bag with her phone, charger, notebook, and pen in it and an encyclopedia “so I can just read until the storm passes.”

She didn’t bring any clothes thinking that she can just easily go home right after the storm subsides. “It has always been that way,” she said.

Marinel and the people of Matarinao village were used to typhoons and long rainy seasons. The fishing village is facing the Pacific Ocean where typhoons frequently develop.

“My father is a fisherman. I grew up not worrying about food, since we are living along the coast with abundant produce. The ocean has always provided for us,” she said.

She said their house has “endured many storms… until super typhoon Haiyan happened.”

At around 3 o’clock in the morning on November 8, 2013, everyone inside the evacuation center was panicking as the winds became more intense.

“I saw a woman carrying her child who almost had her head cut-off by the GI sheets blown away by the strong winds,” said Marinel.

The roof, windows, and doors of the evacuation building also flew and got destroyed. Many people got injured by the broken glass windows and flying debris.

When the storm finally subsided, 11 people were found dead in Matarinao village.

From a survivor into a climate warrior

It was almost noon when the water from the storm surge receded. Marinel couldn’t believe her eyes when she went out of the evacuation center to check their house.

Only a quarter of its flooring and three columns were left. “Everything was gone. Everything in it was washed away by the ocean,” she said.

Marinel said she regrets that she didn’t bring the small box containing “my literary works, and the certificates and medals I earned in school” when they evacuated.

“That box symbolizes who I am, my achievements, my self-worth. Nothing was left of our home. And losing that box felt like losing my identity, my dreams, my significance as a person,” she said.

Marinel’s village was in complete isolation after the destruction of Haiyan. They had no food but root crops, there was no clean water, electricity, and a secured roof over their heads.

“We lost all our clothes so we were all wet and cold. I was only 16 years old back then and I was confused and devastated by the reality I was facing,” she said.

The path to recovery was “thorny and painful.” It took months before Marinel was able to go back to school and more months before their livelihood started to slowly pull through.

Super typhoon Haiyan affected more than 14 million people in 44 provinces across the country, displacing at least 4.1 million people, killing over 6,000 individuals, and leaving nearly 2,000 people missing.

It damaged more than 1 million houses and disrupted the livelihoods of nearly 6 million people. The overall damage is estimated at US$5.8 billion.

The uncertainties in her future path after the near-death experience pushed Marinel to work hard to support her college education and help provide for the family.

“After Haiyan happened, it seemed like my future even became more unsure because my parents did not earn enough to send me to college,” she said.

Fisherfolk, including her father, in Matarinao village, had stopped fishing for months because their boats were broken and there was a significant depletion of marine life.

“People were also hesitant to eat fish at that time. We couldn’t bear the thought of eating fish that may have fed on the dead bodies of our neighbors, and people we know,” said Marinel.

The tide started to turn when she got a college scholarship from an international humanitarian organization, which also commissioned her as a youth facilitator on climate change adaptation and mitigation workshops in Eastern Visayas.

In 2014, she was invited to speak and share her experience in various international climate conferences. In the same year, Marinel was featured in a documentary film, which was released in different countries.

“Sharing my story and the story of my village has become a way of healing for me,” she said.

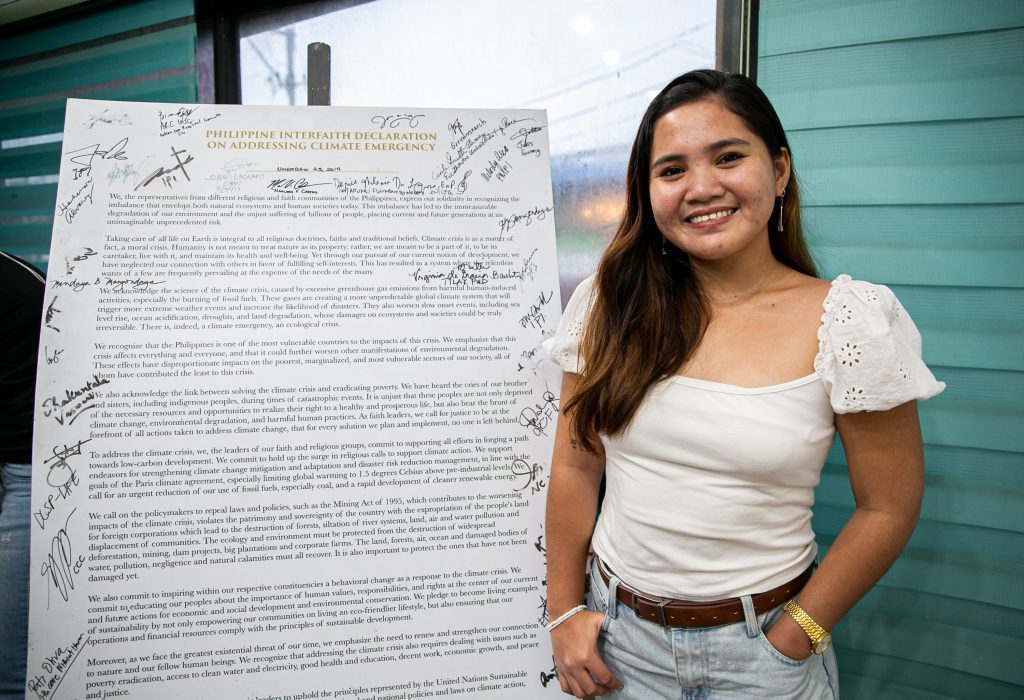

One year after the devastation of Haiyan, Marinel decided to “stand up as a ‘climate warrior’ instead of speaking up as a mere survivor of a climate catastrophe.”

“I realized that Climate Change is not just an issue of destruction and suffering or of adaptation and mitigation, but it is also an issue of human rights,” she said.

Since then, Marinel has been amplifying the voice of vulnerable communities to the climate crisis, not just with the Philippine government and the business sector but in the international community.

She’s been visiting different countries, especially countries in the “Global North,” to appeal to governments and world leaders to “heed the voice of the vulnerable nations.”

In 2015, she attended the United Nations (UN) Conference of Youth (COY) and the Conference of Parties (COP) in Paris, France.

COY is an annual gathering of youth organizations worldwide, which is held a few days before the UN Climate Change Conference or COP.

Marinel and another Filipino environmental activist are going to Milan, Italy in September to represent the Philippines in the Pre-COP26 summit.

She is also the Philippine Country Coordinator of this year’s COY that will be held in Glasgow, Scotland in November 2021.

“We want the carbon majors to acknowledge their accountability for what they have done to us, to my community and other vulnerable communities around the world,” she said.

The youth as “leaders of today”

“Fighting for the young generation’s future” has become Marinel’s commitment. She focused on organizing her fellow youth “to stand together as the voice of the environment.”

In her speech before the US Senate’s Subcommittee on East Asia, the Pacific, and International Cybersecurity Policy hearing on ‘Combating Climate Change in East Asia and the Pacific,’ she urged the youth to “create a bigger impact.”

“Never underestimate our power to make a change but we must do it collectively. We must not stop because the future depends on our decision now,” she said.

Marinel criticized world leaders who always say that “the youth is the future.” She said they’ve failed “to realize that we, the youth, are the ‘present’.”

“Now is the time that we dream and work for a better future. And if they will continue denying us of the future that we deserve, we must sustain the resistance and fight,” she said.

0 Comments